From Guarantee to Gamble: Dismantling MGNREGS and the Cost to Rural India

The repeal of MGNREGS marks a decisive shift from a rights-based employment guarantee to a budget-bound welfare scheme. As the Centre retreats from its constitutional responsibility, the rural poor are left more exposed than ever—economically, socially, and politically.

The decision to repeal the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and introduce the Viksit Bharat – Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Bill, 2025 (VB-GRAMG Bill) is a deliberate departure from the State’s long-standing responsibility to safeguard the rural economy and ensure livelihood security. And the worst part is, it is happening amid an increasingly inequitable economic transformation in the country. A phased dilution of the scheme had been on the cards in recent years, as evident from the declining budgetary allocations for the scheme. Nevertheless, the complete reversal and restructuring of the programme have indeed come as a shock. This shift is likely to trigger serious adverse consequences for the rural poor on a large scale and for the stability of the state’s finances.

As the curtain falls on one of the most thoughtful rural interventions in India’s history, it is essential to recall the context in which the MGNREGS was introduced and the role it has played in sustaining rural livelihoods. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, enacted in 2005, was implemented in a phased manner, beginning from February 2, 2006, initially covering select districts and subsequently implemented nationwide by 2008. It was in the backdrop of widespread rural unemployment and persistent poverty, particularly among historically marginalised communities such as the Scheduled Castes (SCs) and the Scheduled Tribes (STs), that this programme was conceived. It was an imaginative response to the structural failure of labour markets to generate adequate employment for the rural workforce.

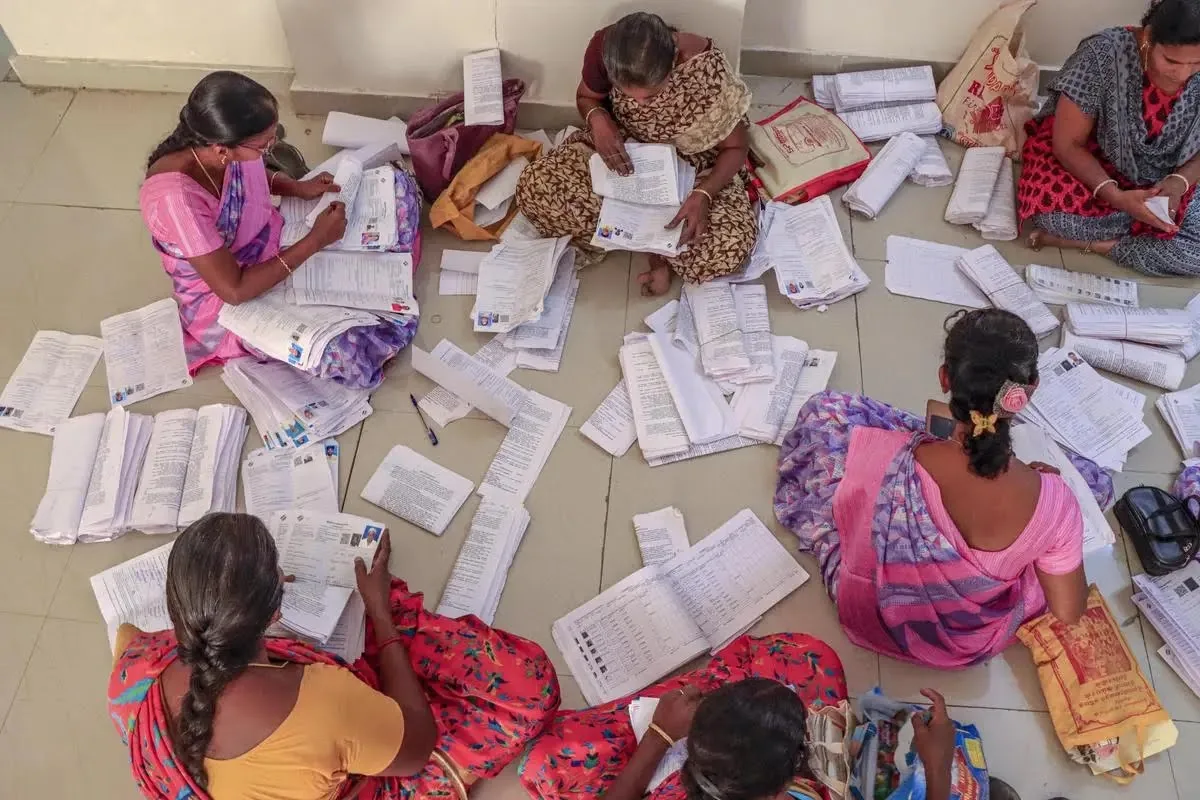

The scheme aimed to enhance livelihood security by guaranteeing wage employment, thereby providing an adequate safety net and strengthening the purchasing power of the rural poor. A key objective was to check distress migration by enabling rural workers to find employment within their own villages rather than migrating to urban centres for uncertain casual work. Equally significant was its emphasis on decentralisation: the Act aimed to deepen democracy and strengthen rural local self-governments by entrusting them with the primary responsibility for planning and implementation. Subsequently, MGNREGS also contributed to the creation of durable rural assets and the conservation of natural resources, which had a cyclic impact on the resilience of rural areas.

The envisaged outcomes of the scheme were quickly justified by the way it cushioned the impact of the economic crisis. MGNREGS was applauded as a crucial economic stabiliser and social safety net during the global financial crisis of 2008. While economies worldwide faced recession and mass unemployment, MGNREGS helped India mitigate the worst impacts, particularly in rural areas. Despite several implementation challenges, the scheme played a significant role in sustaining rural purchasing power, reducing poverty, and empowering workers. Several empirical studies have substantiated this impact.

The newly proposed Bill, however, contradicts the core objective and character of MGNREGS as a universal, demand-driven employment guarantee scheme. This shift appears to weaken the rural economy and potentially precipitate new livelihood insecurities. The mandatory provision of employment, central to the Act’s rights-based framework, has been removed, effectively exempting the Union government from its obligation to allocate funds to the demands of job seekers. Furthermore, a portion of the Centre’s financial responsibility is being transferred to state governments, many of which are already under severe fiscal stress due to the growing burden of unilaterally designed central schemes. For example, Kerala, one of the states that has demonstrated greater efficacy in implementing the MGNREGS, will incur an additional annual burden of around Rs. 2000 crores due to the introduction of a 40 per cent state share.

The introduction of “normative allocation,” under which state-wise expenditure is restricted by the centre and excess costs borne by states, will further limit the programme’s reach. With the scheme being redesigned as supply-driven, the number of days of employment will now depend entirely on annually earmarked funds rather than on workers’ demand, undermining the very idea of employment guarantee.

The proposed framework also raises serious concerns regarding exclusion. The rationalisation of job cards may leave large sections of rural households outside the safety net. Moreover, the provision to suspend employment guarantees for up to sixty days during peak agricultural seasons will be particularly troubling. This would deprive households of an assured income precisely when they are most vulnerable, thereby increasing their dependence on landlords and forcing them to accept lower wages and endure exploitative labour relations. The rural poor, who depend on MGNREGS for an assured income in the event of unexpected distress and shocks, would be further disadvantaged. The condition that employment will be provided only based on planned work at the village level will deny opportunities to marginalised segments of society, who are not part of the mainstream social space.

Taken together, these amendments severely weaken the original rights-based architecture of the Act, transforming a legally enforceable entitlement into a budget-constrained, centrally administered and highly restrictive welfare programme. It is highly deplorable that a widely acclaimed programme, which provided at least a minimal degree of livelihood security, has been called off, at a time when the vulnerabilities of the rural poor are mounting. The withdrawal of this historic programme also aims to erase the legacy of the man after whom it was named.

(OBC strives to present perspectives from across the ideological and social spectrum. The views, opinions, and interpretations expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of OBC).