The Many Woes of the New Labour Codes

The Modi government calls the labour codes long-overdue reforms; trade unions call them “a deceptive fraud.” With weakened safeguards, expanded corporate freedom, and rising worker unrest, the clash over the new regime is now a national reckoning.

“When a multi-millionaire industrialist says that we should extend working hours to 12, we have a government that nods along and says, we will think about it. And that’s exactly what transpired with the new labour codes,” says Muhammad Hashim, Kerala State General Secretary of the youth wing of the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), a trade union affiliated with the Indian National Congress.

Trade unions, including the INTUC, have been on a constant war footing for the last few years against the new labour codes in India. On Friday, November 21, 2025, the Union Ministry of Labour and Employment notified the rules for four Labour Codes. Labour unions across the country — except the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), the labour wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — are protesting against it tooth and nail. Even the BMS has its own reservations about the codes. The joint platform of 10 Central Trade Unions has called it a ‘deceptive fraud’ committed against the working people of the nation in a statement dated November 21.

What are the New ‘Codes’?

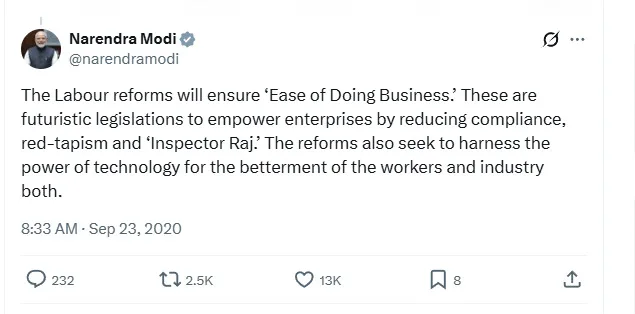

“The ‘long due and much-awaited’ labour reforms are shining examples of Minimum Government, Maximum Governance,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi told the nation through an X (formerly Twitter) post on September 23, 2020, while passing the labour reform bills.

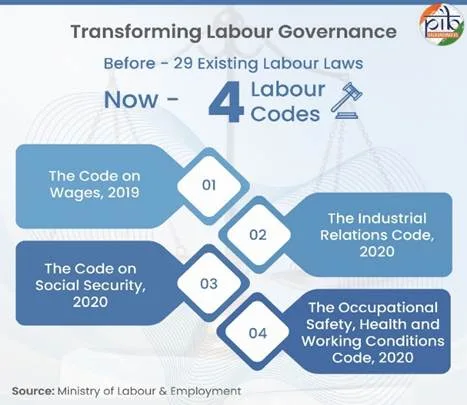

The new codes absorb and repeal 29 existing central labour laws and amalgamate them into four codes: the Code on Wages, 2019; the Industrial Relations Code, 2020; the Code on Social Security, 2020; and the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020.

The government claims that these reforms will bring much-needed simplification to colonial-era laws, as ‘the working class is entangled in a web of multiple labour legislations.’ According to the consolidated document titled ‘New Reforms for New India’ published in the official website of the Ministry of Labour & Employment, the reforms will enhance ‘ease of doing business,’ ‘employment creation,’ and ‘worker productivity.’

Since 2020, when the draft of all four codes was officially notified by the Ministry of Law and Justice, labour unions have been voicing their apprehensions and demanding the repeal of what they call labour-unfriendly codes. General strikes were held back in 2020 along with the Farmers’ Protest in Delhi.

On July 9, 2025, the central trade unions organised a general strike, which they claim saw the participation of 25 crore workers, raising a 17-point charter of demands that included scrapping all four codes. But the government remained ‘obstinately unresponsive,’ the statement from the Joint Platform of Trade Unions says.

A Blow to Federalism

“Labour is a concurrent subject, which means both the Union and the states can make laws pertaining to it. But these codes have been arbitrarily framed by the Union government, ignoring all norms of federalism,” Gopinath K. N , Kerala State Secretary of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), the trade union associated with the CPI(M), told OBC.

Though the government claims that ‘extensive discussions were held before the initiation of labour reforms,’ trade union members told OBC that none of their demands were considered at any stage. Elamaram Kareem, Kerala State General Secretary of CITU and a member of the Labour Standing Committee, said in a social-media video statement that the committee had unanimously recommended several amendments to the provisions in the codes. None of those recommendations were taken into consideration by the Union Government while presenting the draft codes in Parliament, he alleged.

The Bills were passed in Parliament in 2020, amid opposition boycotts and allegations that the process was carried out without proper deliberation.

Decent wages or ‘Floor Wages’?

“The minimum wage in Kerala for unskilled workers is about ₹800 a day. The new code sets a national floor wage of ₹202 and says no state can fix wages below this. But an employer can choose to pay only the floor wage and ignore the state’s higher minimum wage — and they won’t face any action, because only the national floor wage is legally binding” Gopinath explains.

According to the Union Labour Ministry, the provision of a centralised ‘floor wage’ has been introduced in the Code on Wages to remove regional disparity in minimum wages. The states can set higher limits subject to requirements.

“When countries around the world are talking about decent living wages, this government is talking about a ‘floor wage’ that doesn’t even sustain a basic living,” Hashim adds to the concern.

A blindfold or a promise of job security?

Another contentious change is the introduction of fixed-term employment — contracts for a set period, with benefits given only for the duration worked. Trade unions say this destroys permanent employment. Once the contract ends, the worker can be terminated without any right to continue or even approach the courts. Renewal depends entirely on the employer’s discretion, and, as Kareem points out, no employer will retain a worker who asserts their rights. “This will create a set of ‘slave’-like workers in our workplaces,” warns Elamaram Kareem.

“It is akin to the Agniveer scheme, where recruitment to the Armed Forces was for a period of four years, with a possibility to be extended,” K. N Gopinath added.

Crippling the Unions

“Earlier, an internal inquiry was mandatory before dismissing any employee from the workplace. The new provisions do not require this. They have crippled trade unions of all their rights and collective bargaining power,” T. B. Mini, State Secretary of the Trade Union Centre of India (TUCI), the trade union wing of CPI (ML) Red Flag, told OBC.

The threshold for lay-off, retrenchment, and closure has been raised from 100 to 300 workers, meaning establishments with up to 300 employees can now retrench staff without prior notice or government approval. The codes also promise universal social security, but unions say loopholes allow employers to label workers “unfit” and deny benefits — a move they see as weakening collective bargaining and paving the way for union-free workplaces.

Mini also observes that only unions with 51% membership will be recognised as the Negotiating Union, allowing employers to deal with just one union and sideline the rest. A 14-day advance notice for strikes and lockouts is now mandatory, and the expanded definition of “strike” even includes mass casual leave.

An end to ‘Inspector Raj’?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly claimed that the new labour codes will empower enterprises by reducing red tape and ending the “inspector raj.” But Gopinath argues the opposite, calling the codes “a hidden tool to dilute the powers of labour officers.”

“Earlier, in employment disputes, we held tripartite discussions between the employee, employer and labour officer. The officer could penalise management for violations. Now they can only ‘advise’—and employers can ignore them even while breaking the law,” he says.

The Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020, states that inspectors will act as facilitators “to help employers comply with the law” rather than police them.

Safety as a ‘token’

The mandatory safety provisions for workers in the new code have been raised from establishments with 100 employees to those with 300 employees. This means a large number of companies now fall outside the ambit of protections that were earlier available under the Factories Act, 1948. Even major companies like Hindalco may get exempted from these requirements, says Gopinath.

The Act also introduces the formation of Safety Committees with employer–worker representation — but only establishments with 500 or more workers are required to constitute them.

The State in a Spot

Following an online meeting with trade union representatives, Kerala Labour Minister V. Sivankutty announced that the state would not implement the new labour codes and would ask the Centre to withdraw them. But unions like TUCI allege the government invited only “centrally recognised trade unions,” sidelining other major unions in the state. “This is exactly what the Centre has done, and it is what we are protesting against. Excluding the strong unions here is not a welcome move,” Mini said.

The government had earlier faced criticism for notifying draft regulations in 2021, though Sivankutty said states were instructed by the Union government to frame rules and that Kerala has not acted on them since.

A Larger Move towards Corporatisation

Contenders argue the labour codes are part of the Modi government’s broader push toward corporatisation, prioritising corporate interests over workers’ rights. Protests are spreading nationwide while the Centre remains silent.

Trade unions have also been demanding the reconvening of the Indian Labour Conference (ILC), the top tripartite forum for deliberating labour policy, which has not met since 2015. A reform of this scale required discussion there, but the Centre has avoided it.

At a time when daily wage earners have accounted for the highest share of suicides for five consecutive years (NCRB), genuine protections—not cosmetic reforms—are essential. Whether the government, which previously rolled back the farm laws after a year-long protest, will respond to workers’ collective pressure remains uncertain.