When Laws Aren’t Enough: Kerala’s Anti-Dowry Enforcement Gap

Kerala has Dowry Prohibition Officers in every district, yet most report fewer than 10 complaints a year—even as dowry-related deaths persist. A recent PIL before the Kerala High Court has exposed deep gaps in implementation and public awareness, prompting the state to propose amendments to the Dowry Prohibition Act, including decriminalising the giving of dowry.

As the debate resurfaces, OBC examines how weak enforcement and social pressures continue to leave women vulnerable despite the law.

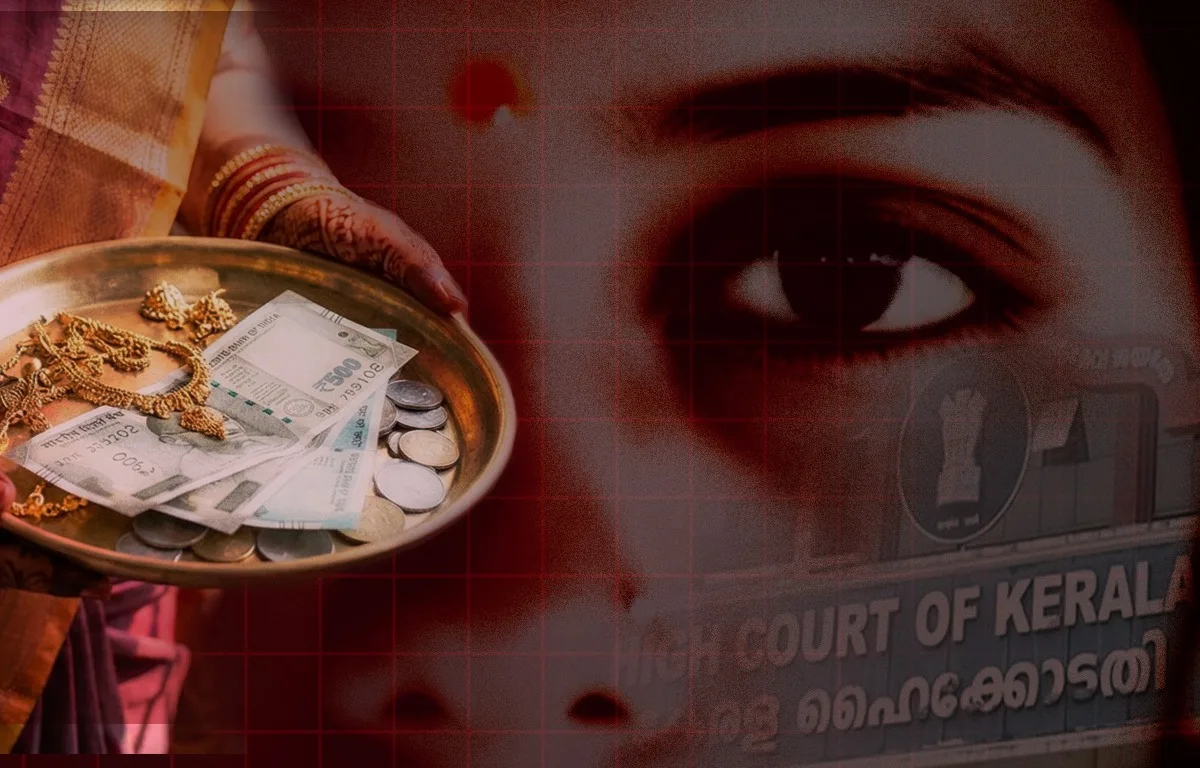

“They used to say the wedding was not grand enough, that the dowry was insufficient. They called me homeless and broke, and said I lived by begging for money. I was beaten like a dog, denied food, and thrown out of the house when I was seven months pregnant,” wrote Vipanchika Maniyan in her suicide note, hours before she died by suicide on July 8, 2025. A native of Kerala’s Kollam district, Vipanchika and her one-year-old daughter were found dead in their apartment in Sharjah. The victim’s family had accused her husband, Nidheesh Valiyaveettil, and his relatives of physical and mental harassment. In a complaint to Kerala Police, Vipanchika’s mother alleged persistent dowry harassment and racial abuse by her husband and in-laws.

Just days before this incident, the Supreme Court had suspended the jail sentence of Kiran Kumar and granted him bail—the man convicted in the dowry-related death of his wife, Vismaya V Nair, who died in 2021. Later that month, on July 29, another woman, Athulya Sekhar, died by suicide, allegedly after facing dowry-related harassment since her marriage. Another Kollam native, Athulya was also found dead in her Sharjah apartment. According to her family, she died by suicide after enduring 12 years of physical and mental abuse by her husband, Satheesh Sankar. The family shared videos showing Satheesh physically assaulting Athulya. Days before her death, Athulya allegedly told her cousin in a voice note that Satheesh had kicked her in the stomach, leaving her unable to move.

A string of dowry-related deaths shook Kerala in 2021 as well. Police records show 43 such deaths between 2020 and 2025.

Kerala has mechanisms in place to prevent and address dowry complaints under the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, including Dowry Prohibition Officers across all 14 districts.

Yet, the dowry prohibition officers in several districts said they received zero complaints for nearly a year.

Why does a state that continues to report alarming numbers of dowry deaths have its system for prohibiting the menace in such disarray? How is this preventive and redressal mechanism meant to work—and where does it fall short?

As debates around dowry are reignited, OBC unpacks the realities of how the dowry prohibition system works in the state.

A petition that sparked fresh conversations

The Kerala government recently informed the High Court on January 21 that the Law Reforms Commission has proposed a draft amendment to the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. The proposal seeks to decriminalise the giving of dowry while encouraging survivors to report dowry-related abuse. The state made this submission in response to a public interest litigation (PIL) filed in July 2025 by Tellmy Jolly, a law graduate and public policy professional.

In the PIL, the petitioner argues that the implementation of the Kerala Dowry Prohibition Rules, 2004, remains inadequate. She contends that the absence of a functioning machinery to investigate complaints, conduct awareness campaigns, or maintain records of offences has contributed to the failure to prevent dowry harassment and deaths. “The failure of the State to effectively implement the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, and the Kerala Dowry Prohibition Rules, 2004, results in the denial of a woman’s right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution.”, it says.

On paper and on the ground

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961, the Dowry Prohibition (Maintenance of Lists of Presents to the Bride and Bridegroom) Rules, 1985, and the Kerala Dowry Prohibition Rules, 2004 are the main laws governing dowry in the state.

Under the Act, “dowry” refers to any property or valuable security given or promised—directly or indirectly—by either party to a marriage, their parents, or any other person, to the bride, groom, or anyone else, either before, during, or after the marriage, in connection with the marriage.

Section 8B of the Dowry Prohibition Act provides for the appointment of Dowry Prohibition Officers (DPO) and defines their jurisdiction. In Kerala, DPOs were first appointed in 2004 in three regions—Thiruvananthapuram, Ernakulam, and Kozhikode—under the Kerala Dowry Prohibition Rules. The 2021 amendment to the Rules mandates DPOs in every district. The District Women and Child Development Officer functions as the Dowry Prohibition Officer of the respective district.

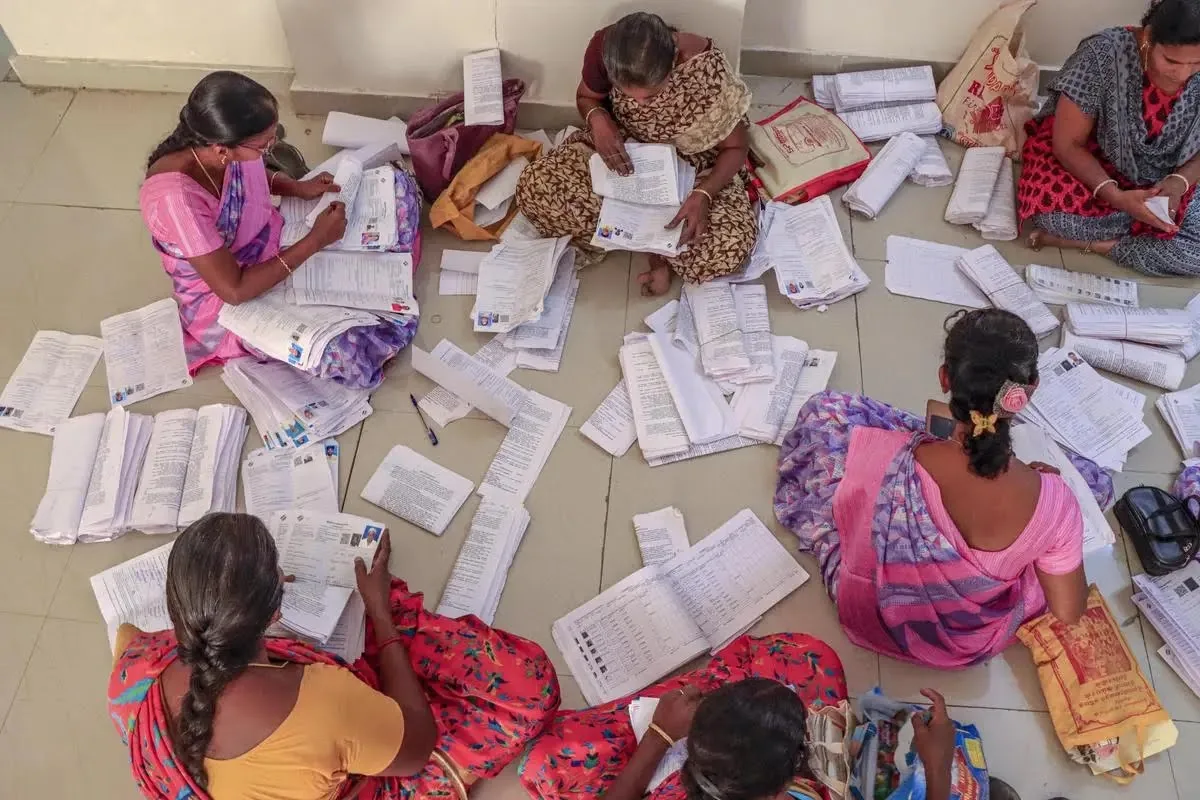

Upon receiving written complaints—online or in person—a notice is issued to both concerned parties. An inquiry is then initiated, followed by a hearing where both sides are called. Based on this, a decision is taken on how the case will be handled.

The petitioner Tellmy Jolly also submitted RTI applications seeking information on several aspects of dowry prohibition, including details of DPOs across all districts, their quarterly work reports, and the number of complaints filed with them. However, she says the data provided was scattered, making follow-ups practically impossible. “There is a lack of a uniform or centralised mechanism—that’s what I feel. They did not give proper numbers that could be helpful for the petition,” Tellmy told OBC.

As per the rules, quarterly reports are to be submitted by the Dowry Prohibition Officer to the Chief Dowry Prohibition Officer, detailing the number of complaints received and the actions taken. However, the PIL states that the implementation of these provisions has been inadequate. The Kerala High Court had sought instructions from the State government regarding the publication of data on the number of complaints received and the action taken in relation to dowry demand incidents in July 2025, in connection with the PIL.

The realities on the ground reflect these concerns.

Reading the available data

Across districts, the reporting of dowry-related complaints to DPOs remains abysmally low. All the officers OBC reached out to said the number of complaints they received over a span of around one year was fewer than 10.

Kottayam reported an estimated one to two cases, while Ernakulam recorded around four over the past year, according to the respective DPOs. Alappuzha recorded no complaints.

“In Ernakulam, the recent cases we handled were mostly from divorced women seeking the return of gold and money from their ex-partners. Most of these complaints are already sub judice. This is a challenge we face: when cases are under court consideration, there is little we can do in parallel. Otherwise, we call the parties for a hearing, conduct an enquiry, and forward the matter to the DySP if needed.” the Dowry Prohibition Officer of Ernakulam district said. She added that no cases related to ongoing dowry harassment or violence seeking intervention had been reported from the district in the past year since she assumed office.

This stands in stark contrast to earlier reports, which suggested that southern districts including Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Pathanamthitta, Alappuzha, Kottayam, Idukki, and Ernakulam accounted for up to 80 percent of the total dowry harassment related cases registered with the Kerala State Women’s Commission since 2010. An earlier report had attributed the tepid response to a lack of public awareness about the existence of such offices—a finding that appears to hold true based on what is emerging here.

Awareness gaps, social barriers

Under the Act, DPOs are tasked with creating public awareness, conducting inspections and inquiries into violations, maintaining registers of complaints and outcomes, and receiving complaints from aggrieved individuals or organisations. In practice, this role has largely been reduced to a procedural formality.

Awareness campaigns are conducted in schools and colleges as part of routine work. However, there is no stipulated frequency for how many such programmes must be held each month. “We regularly conduct campaigns and awareness classes around churches, mosques, temples, wedding auditoriums, and other spaces centred on marriages,” one officer said. But preventive measures largely remain limited to collecting anti-dowry declaration forms from state government employees. Free legal aid is also provided to the needed victims, she added.

Activist and lawyer Asha Unnithan told OBC that the presence of this machinery has not figured in any of the cases she has handled. Its working methods remain largely unknown even to those actively engaged in this field.

“There are powers and duties conferred on Dowry Prohibition Officers under the existing Rules, including conducting house visits. The question is how far these are being enforced,” said advocate Thulasi K Raj, lawyer and counsel for the petitioner Tellmy Jolly. She added that low reporting may also be shaped by socio-political factors, where dowry continues to be viewed as a “personal issue” between husband and wife rather than a social one.

This is what prompted the petitioner to challenge the constitutional validity of Section 3 of the Act, which criminalises the giving of dowry on par with taking it. She argues that it is often societal pressure that compels a bride’s family to comply. This inherent flaw in the law is now under scrutiny, she said.

The Kerala State Women’s Commission had earlier urged the government to regulate wedding expenses and strictly enforce the Dowry Prohibition Act. It has proposed mandatory disclosure of marriage expenses to District Dowry Prohibition Officers, along with monitoring by local bodies. The Dowry Prohibition Rules also stipulate that both the bride and groom must maintain a list of presents exchanged at the time of marriage, which can be inspected by officers. “Usually, none of the couples do that,” Thulasi said.

“Parents of brides are often coerced into giving dowry, and it is also socially perceived as a token of love for their daughter. The Women’s Commission has participated in discussions on the government’s proposal to decriminalise it, and we believe it should not be a crime. However, strict action will be taken against those who receive dowry,” P. Satheedevi, Chairperson of the Kerala Women’s Commission, told OBC. She added that low reporting to DPOs may stem from families’ fear of incriminating themselves, but said this could change positively with the proposed amendment.

As debates around dowry resurface in Kerala, the gap between law and practice grows ever more evident. Despite the structures, officers, and rules intended to protect women, systemic inertia, procedural formalities, and social pressures continue to leave victims and potential victims vulnerable.The pressing question is whether the proposed amendments will ensure proper enforcement of the laws, while also addressing the societal dimensions of the issue.