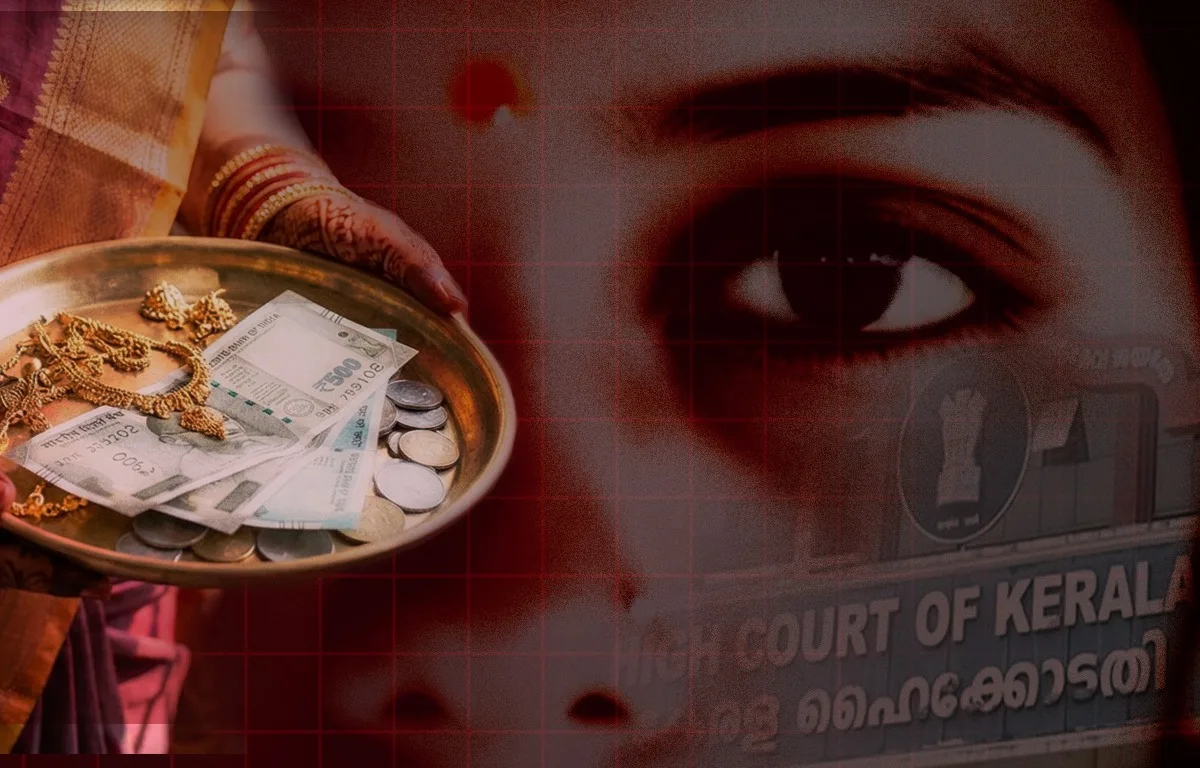

Where the Case Dies: Why So Few Rape Complaints Lead to Conviction in India

The verdict in the Kerala actor assault case is a grim reminder of why most rape cases in India never end in conviction. India’s abysmal rape-conviction rates reveal systemic failures: slow investigations, weak forensic practice, witness attrition, and routine collapse of cases as witnesses turn hostile.

Every year India recorded tens of thousands of rape complaints; yet only a fraction end with a guilty verdict. The National Crime Records Bureau’s data confirm the paradox: large numbers of reported offences but persistently low conviction outcomes. Experts, court judgments and forensic studies point to a chain of institutional failures. NCRB’s ‘Crime in India’ reports and subsequent tabulations show the scale: tens of thousands of rape cases are recorded each year and conviction rates sit well below 50% — historically in the mid-to-high twenties in recent annual summaries. In plain terms, roughly only three of every ten reported rape cases end up in conviction.

That is not just a number; it is a directional signal of where the pipeline in criminal justice fails survivors-investigation, collection of evidence, prosecution, protection of witnesses, and courtroom adjudication.

The system’s slow bleed

A foundational, widely-cited diagnosis comes from empirical work on ‘attrition’ — how cases “fail to reach, or progress through” the system. The Oxford Law study on attrition explains the concept plainly: “Attrition refers to the process by which criminal cases fail to reach, or progress through the criminal justice system.” That process includes non-registration of complaints, poor investigation, delayed charge-sheets, withdrawals or retractions by victims, and acquittals at trial.

In other words, the largest number of cases is lost before trial verdicts are written-even before, during those stages of gathering evidence and securing or silencing witnesses.

Where investigations go wrong: police, medicine and forensics.

In several cases, Police fail to record or investigate complaints with the sensitivity and speed required for sexual-offence cases; initial inquiry errors can be irrecoverable. The Sakshi judgment (2004) warned that narrow, technical approaches by authorities deny survivors access to justice and stressed victim-sensitive procedures. ‘Limiting the understanding of ‘rape’ to abuse by penile/vaginal penetration only, runs contrary to the contemporary understanding of sexual abuse law’ the bench consisting of Justice C P Mathur and Rajendra Babu, the then Chief Justice of the Supreme Court observed.

Forensic evidence—so often imagined as decisive—is more often undermined by delay, poor collection, and fragile chain-of-custody practices. A recent forensic commentary opines that ‘delays in forensic reporting, inadequate infrastructure, and trained manpower shortage compound the predicament,’ thereby weakening the probative value of DNA and related tests. ([Indian Journal of Medical Ethics). DNA profiling, while scientifically reliable, is treated as corroborative rather than conclusive because of risks like sample contamination, inconsistent protocols, and deviations in collection/preservation.

Courts prioritize traditional evidence like eyewitness testimony over DNA unless protocols are standardized, infrastructure improved, and judges sensitized to forensic advances.

The courtroom calculus: credibility, consistency and a high bar

Courts require proof beyond a reasonable doubt. In principle, the Supreme Court has recognised that a reliable single witness — the prosecutrix — can sustain a conviction. In practice, defence strategies that emphasise minor inconsistencies, delays in lodging complaints, or lack of forensic corroboration often persuade judges to acquit. The Nirbhaya (Mukesh) case showed how forensic corroboration together with consistent testimony can secure conviction — but it is an outlier precisely because the investigation and trial were unusually rigorous and high-profile.

Beyond police and science lies the social reality: victims and witnesses face stigma, threats, inducements to “compromise” and extreme family pressure. The Oxford attrition analysis underlines this social vector: attrition is not just procedural but deeply social — many cases are effectively turned off by the environment surrounding reporting and trial.

What reformers say would change conviction maths

Policy researchers, NGOs and judges recommend a package approach: rapid-response forensic teams, specialised sexual-crime units within police, more fast-track courts for sexual offences, robust witness-protection and psycho-social support for complainants, and institutional audits of investigation quality. The evidence suggests raising conviction rates requires ‘fixing multiple links at once’ — improving just one (say, more courts) without strengthening police forensics and witness protection will have limited effect.

Two landmark judgments — Sakshi v. Union of India (2004) and Mukesh & Anr v. State (NCT of Delhi) — remain pivotal not only for the doctrines they established but for what they revealed about the systemic reforms needed to turn complaints into prosecutable cases. Sakshi pushed the criminal-justice system toward a more survivor-centred approach by directing police, prosecutors and courts to conduct victim-sensitive investigations, avoid retraumatising testimony practices, and interpret sexual-offence provisions in a way that reflects the lived realities of abuse. A decade later, the Nirbhaya case illustrated the other side of the equation — how swift action, meticulous evidence collection, proper chain-of-custody procedures, and robust forensic corroboration can translate into a legally airtight prosecution. Read together, the two decisions form a quiet blueprint for reform. They show that justice in sexual-assault cases is not achieved by legislation alone but by the day-to-day discipline of the system — acting quickly at the FIR stage, preserving medical and digital evidence without delay, and ensuring that witnesses are protected long enough for the truth to withstand the pressures of trial.

Numbers and their meaning

Statistics — NCRB tables, conviction percentages — matter because they show system performance. But behind the percentages are human choices and institutional design: whether a police station treats a survivor with dignity; whether a medical officer does a timely MLC (medico-legal case) and preserves samples; whether a court timetable protects a traumatised witness from attrition. Fixing where cases die means redesigning practice, training, infrastructure and social supports — simultaneously. The Oxford study’s notion of attrition is both diagnosis and roadmap: stop the bleed at every stage, and more convictions will follow.

Shahina K K

Shahina K.K. is a seasoned journalist and the co-founder and chief editor of OBC. She has received the International Press Freedom Award (2023) and the Chameli Devi Jain Award, among others. Her work is known for its depth, and steadfast commitment to speaking for the margins and defending democracy

View all posts by Shahina K K